“The way we speak about ourselves shapes how we see ourselves.” This simple truth underscores the profound impact language has on identity and self-perception. For neurodivergent individuals, the words used to describe their experiences can either empower them or reinforce harmful stereotypes. Imagine the difference between being called “quirky” versus “weird,” or hearing yourself described as “broken” instead of “unique.” The language we choose doesn’t just reflect our attitudes—it actively shapes them.

Neurodiversity is the idea that brain differences, like autism, ADHD, and other neurodivergent conditions, are natural variations of the human experience rather than deficits to be fixed. It challenges us to see beyond the labels society often imposes and to celebrate the value of diverse ways of thinking. But how we talk about neurodiversity plays a crucial role in whether this concept fosters inclusion or unintentionally perpetuates exclusion.

In this blog, we’ll explore why language matters in the context of neurodiversity, examining examples of empowering versus harmful terms and phrases. We’ll also discuss how intentionality in communication can build understanding and strengthen advocacy efforts. By the end, you’ll see how even small changes in the way we speak can create a ripple effect of acceptance and belonging.

The Power of Language in Shaping Perceptions

The words we use to discuss neurodiversity shape how society perceives it. Language has the power to frame neurodivergent traits and experiences as either strengths to celebrate or challenges to pity or fix. This framing directly influences public understanding, attitudes, and policies.

1. Language Creates Perception

When neurodivergence is described using deficit-based terms—like “disorder,” “dysfunction,” or “problem”—it perpetuates the idea that these differences are inherently negative. Phrases such as “suffering from autism” or “struggling with ADHD” imply constant hardship, overlooking the strengths and unique perspectives neurodivergent individuals bring to the table.

Conversely, terms like “neurodivergent” or “brain differences” encourage a neutral or positive understanding. They position neurodiversity as a natural variation, much like diversity in race, culture, or gender, fostering a sense of inclusion rather than marginalization.

2. Language Shapes Attitudes and Behavior

When people are exposed to affirming language, they are more likely to develop empathetic and supportive attitudes. For example:

- Positive framing: Referring to someone as having “unique problem-solving skills” or “a creative perspective” shifts the focus to their strengths.

- Negative framing: Using terms like “low-functioning” or “high-functioning” not only oversimplifies complex experiences but also creates hierarchies within neurodivergent communities.

Public behavior follows these attitudes. Support for inclusive policies, accommodations, and representation grows when people view neurodivergence as a valued part of human diversity.

Media and Education as Amplifiers

The media, schools, and healthcare providers play critical roles in reinforcing public understanding through their word choices. A child growing up hearing autism described as a “gift” will likely approach neurodiversity with curiosity and respect, whereas one exposed to language like “burden” or “tragedy” may develop fear or misunderstanding.

By choosing words intentionally, we can shape a society where neurodivergent individuals feel valued and empowered. Language isn’t just about communication—it’s a tool for shaping perceptions and building a more inclusive world.

How Certain Terms Perpetuate Harmful Stereotypes

Certain terms, when used to describe neurodivergence, can unintentionally reinforce harmful stereotypes by framing differences as deficits or abnormalities. These stereotypes affect how neurodivergent individuals are perceived and treated by society, often limiting their opportunities and undermining their self-worth. Here’s how specific language choices perpetuate these stereotypes:

1. The Term “Disorder” and Its Negative Connotations

-

Framing neurodivergence as inherently negative:

The word “disorder” implies dysfunction or a problem needing correction. For example, calling autism “Autistic Spectrum Disorder” or ADHD “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder” highlights challenges rather than strengths. This framing can overshadow the value of traits like creativity, hyperfocus, or unique perspectives.

-

Impact on public perception:

Hearing “disorder” primes people to view neurodivergent individuals as broken or incapable, fostering pity rather than understanding and respect.

2. “High-Functioning” and “Low-Functioning” Labels

-

Creating a false hierarchy:

These terms oversimplify the complex experiences of neurodivergent individuals by reducing them to how well they meet societal norms. “High-functioning” dismisses struggles, while “low-functioning” devalues the person’s abilities.

-

Reinforcing stereotypes:

These labels can lead to assumptions that some individuals are more “worthy” of support than others, perpetuating inequities in access to resources and accommodations.

3. “Suffering From” or “Afflicted By”

-

Depicting neurodivergence as a tragedy:

Phrases like “suffering from autism” or “afflicted by ADHD” suggest constant hardship and unhappiness, framing neurodivergent lives as inherently less fulfilling.

-

Effect on advocacy and identity:

This language can discourage individuals from embracing their neurodivergent identity and can lead to feelings of shame or inadequacy.

4. Outdated or Derogatory Terms

-

Historical baggage:

Terms like “Asperger’s Syndrome” carry harmful associations due to their links to Hans Asperger’s problematic history. Similarly, outdated terms like “retarded” or “special needs” can evoke negative stereotypes rooted in ignorance or ableism.

-

Modern alternatives:

Using “Autism Spectrum Condition” or simply “autism” is more neutral and avoids unnecessary baggage, while terms like “neurodivergent” emphasize diversity without judgment.

5. Infantilizing Language

-

Undermining autonomy and competence:

Referring to adults as “kids at heart” or treating neurodivergent individuals as perpetual children implies that they cannot achieve independence or maturity.

-

Encouraging stereotypes:

This language can reinforce the myth that all neurodivergent individuals are incapable of self-advocacy, fueling exclusion from decision-making processes.

Why This Matters

Why This Matters

These harmful terms don’t just reflect societal attitudes—they actively shape them, influencing how neurodivergent individuals are treated in workplaces, schools, and healthcare systems. By avoiding deficit-based language and adopting more inclusive terms, we can help challenge these stereotypes and build a more accepting and equitable world.

Identity-First vs. Person-First Language

Defining the Two Approaches

- Identity-First Language (IFL)

- This approach puts the identity at the forefront, reflecting pride and ownership of that aspect of oneself.

- Example: “Autistic person” or “ADHD individual.”

- Key Perspective: Many people see their neurodivergence as an integral part of who they are, much like their nationality or gender. They believe separating their identity from their neurodivergence diminishes its importance or invalidates their lived experience.

- Person-First Language (PFL)

- This approach emphasizes the individual before their condition or identity, aiming to promote humanity over labels.

- Example: “Person with autism” or “individual with ADHD.”

- Key Perspective: Advocates for PFL often argue that this phrasing reduces stigma by focusing on the person first, rather than defining them by their neurodivergence.

The Ongoing Debate

Both approaches stem from the desire to foster respect and inclusion, but they reflect different philosophies about identity and language.

- Proponents of Identity-First Language:

- Ownership and pride: Many within neurodivergent communities see their identity as inseparable from who they are. For example, autistic individuals may view autism as a core aspect of their being, shaping their worldview and experiences.

- Avoiding stigma: IFL resists the notion that neurodivergence is something to be ashamed of or something separate from the person. It asserts that being neurodivergent is not a negative trait.

- Proponents of Person-First Language:

- Humanizing focus: PFL advocates argue that it highlights the person’s humanity, avoiding reductionist views that define people solely by their neurodivergence.

- Historical context: PFL arose in response to stigma, aiming to counteract the dehumanizing language often used in medical and societal settings.

Why Listening to Individual Preferences Is Key

The debate underscores the importance of respecting personal and community choices:

- Personal identity is complex: People’s preferences for how they are referred to may depend on their lived experiences, culture, and personal views.

- Example: Some autistic people strongly identify with IFL, while others prefer PFL to emphasize their individuality beyond autism.

- Community differences: Even within the same community, there is diversity in how people identify. For instance, the autism community tends to favor IFL (“autistic person”), while some disability advocates favor PFL (“person with a disability”).

Empowering Words: Embracing Neurodivergence Positively

Print Empowering Words PDF Infographic

Words shape the way we see the world—and ourselves. When it comes to neurodiversity, the language we choose can either reinforce stereotypes or help dismantle them, paving the way for greater acceptance and understanding. Empowering words acknowledge the value and strengths of neurodivergent individuals, framing their experiences as part of the natural diversity of human life rather than as deficits or disorders to be fixed.

Words shape the way we see the world—and ourselves. When it comes to neurodiversity, the language we choose can either reinforce stereotypes or help dismantle them, paving the way for greater acceptance and understanding. Empowering words acknowledge the value and strengths of neurodivergent individuals, framing their experiences as part of the natural diversity of human life rather than as deficits or disorders to be fixed.

Finding empowering words starts with shifting our focus from what neurodivergent individuals lack to what makes them unique. It’s about replacing deficit-based terms with language that celebrates diversity, encourages inclusion, and fosters a sense of pride. In this way, words become tools for advocacy, connection, and meaningful change, opening the door to a society that recognizes the full potential of every individual. Take a look at these examples of empowering words and different alternatives that can be harmful.

- “Neurodivergent”

- Why it’s empowering: This term is inclusive and neutral, emphasizing natural diversity in brain functioning without negative connotations.

- Harmful alternative: “Mentally ill” or “disordered,” which frame neurodivergence as a flaw or pathology.

- “Unique learning style”

- Why it’s empowering: It highlights individual strengths and capabilities, acknowledging that traditional methods may not suit everyone.

- Harmful alternative: “Learning deficit,” which reduces an individual’s potential to a single limitation.

- “Support needs”

- Why it’s empowering: It focuses on providing help without judgment, reframing assistance as a universal and human requirement.

- Harmful alternative: “Dependent” or “burdensome,” which imply weakness or inadequacy.

- “Diverse abilities”

- Why it’s empowering: It shifts attention to what individuals can do, encouraging appreciation of their strengths.

- Harmful alternative: “Disabled” (when used pejoratively or dismissively), which focuses on perceived deficiencies.

Harmful Language to Avoid

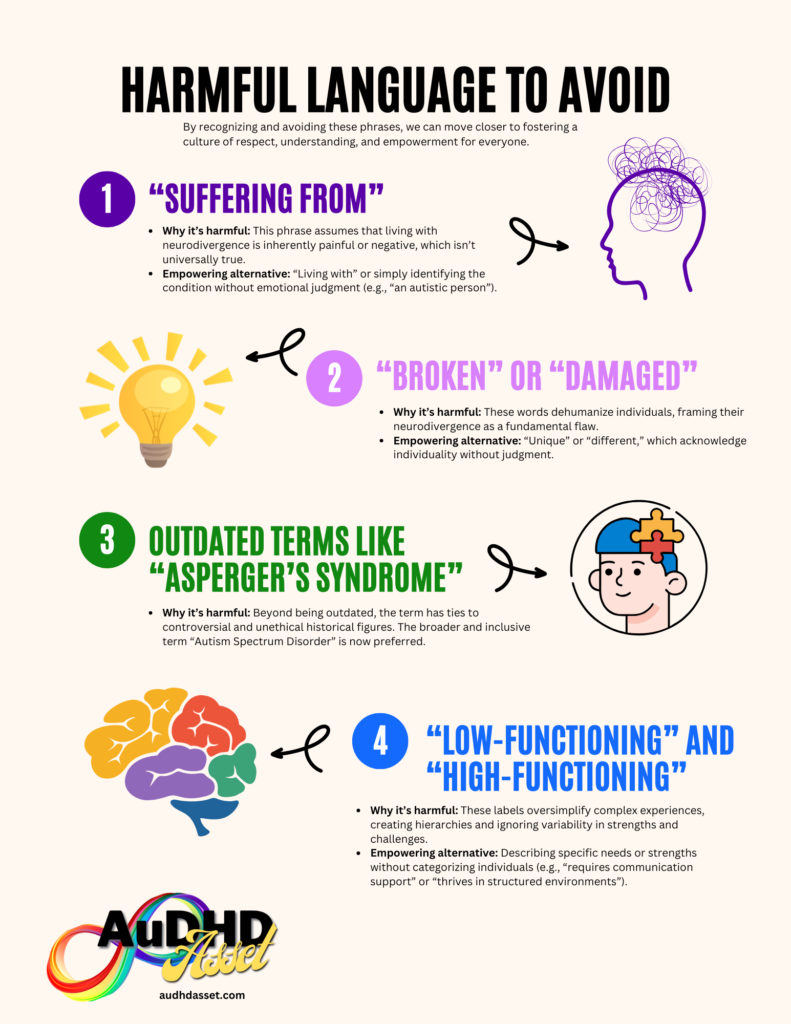

By recognizing and avoiding these phrases, we can move closer to fostering a culture of respect, understanding, and empowerment for everyone.

- “Suffering from”

- Why it’s harmful: This phrase assumes that living with neurodivergence is inherently painful or negative, which isn’t universally true.

- Empowering alternative: “Living with” or simply identifying the condition without emotional judgment (e.g., “an autistic person”).

- “Broken” or “damaged”

- Why it’s harmful: These words dehumanize individuals, framing their neurodivergence as a fundamental flaw.

- Empowering alternative: “Unique” or “different,” which acknowledge individuality without judgment.

- Outdated terms like “Asperger’s Syndrome”

- Why it’s harmful: Beyond being outdated, the term has ties to controversial and unethical historical figures. The broader and inclusive term “Autism Spectrum Disorder” is now preferred.

- “Low-functioning” and “high-functioning”

- Why it’s harmful: These labels oversimplify complex experiences, creating hierarchies and ignoring variability in strengths and challenges.

- Empowering alternative: Describing specific needs or strengths without categorizing individuals (e.g., “requires communication support” or “thrives in structured environments”).

How Subtle Shifts in Language Make a Big Difference

- Changing Perceptions:

Empowering language reframes neurodivergence as a valued part of diversity, reducing stigma and promoting acceptance. For example, calling someone “neurodivergent” rather than “mentally ill” encourages society to view differences with curiosity and respect. - Fostering Inclusion:

Words like “support needs” rather than “dependency” shift the focus to how society can adapt, fostering environments where neurodivergent individuals feel welcome and capable. - Boosting Self-Esteem:

The way people are described influences how they see themselves. Hearing “unique learning style” instead of “learning deficit” helps individuals focus on their potential rather than internalizing shame or inadequacy.

By being intentional with our words, we can help create a world where neurodivergence is seen not as something to “fix,” but as something to value and embrace.

The Role of Intentionality in Communication

When it comes to communicating about neurodiversity, intentionality is key. Being mindful of the language we use is not just about being politically correct—it’s about showing respect for people’s identities, experiences, and preferences. As we strive for a more inclusive society, it’s important to listen, learn, and adapt our language to reflect the values and wishes of the neurodivergent community.

Listen and Learn: Respecting Individual and Community Preferences

Each person’s experience of neurodivergence is unique, and the way they wish to be identified or described may vary. For example, some autistic individuals may prefer identity-first language, like “autistic person,” because they see autism as a central part of who they are. Others may prefer person-first language, such as “person with autism,” as it emphasizes their humanity over their diagnosis. It’s crucial to respect these preferences and avoid making assumptions based on stereotypes or generalizations.

Evolving Language: Terms Change Over Time

Language is not static. As society becomes more aware and accepting of neurodivergence, the terms we use to describe it are constantly evolving. Words that were once widely accepted may no longer be appropriate, and new terms may arise that better reflect current understandings of neurodiversity. For example, the term “Asperger’s Syndrome” has fallen out of favor in favor of the more inclusive “Autism Spectrum Disorder,” due to historical context and its exclusionary implications. Keeping up with these changes helps us stay aligned with the evolving views of the neurodivergent community.

Practical Tips for Intentional Communication

- Avoid Making Assumptions:

When you encounter someone with a neurodivergent condition, avoid assuming how they would like to be described. Rather than using a label based on your own understanding, ask them directly how they identify or what terms they prefer. This small act of respect can have a huge impact on how valued and seen a person feels. - Engage with Neurodivergent Communities:

Staying updated on preferred terminology requires ongoing engagement with neurodivergent communities, advocacy groups, and educational resources. These communities often lead the way in defining language that empowers and accurately represents their experiences. By listening to their voices, you can become an ally and advocate for more inclusive communication practices.

Through intentional, respectful, and ever-evolving communication, we can help create a more inclusive environment where neurodivergent individuals are empowered to live fully and authentically.

Why Words Matter for Advocacy and Inclusion

Language is not just a means of communication—it’s a tool for shaping societal attitudes and driving change. The words we choose, especially when talking about neurodivergence, have the power to foster inclusion, reduce stigma, and create a culture where every individual feels valued and understood. By adopting inclusive language, we can support advocacy efforts that make real, lasting differences in the lives of neurodivergent people.

Creating a Culture of Acceptance

Creating a Culture of Acceptance

Inclusive language is essential in fostering a culture of belonging. When we use language that acknowledges and celebrates neurodivergent individuals, we send a message that they are just as important and capable as anyone else. Terms that empower and affirm neurodiversity—such as “neurodivergent” rather than “disordered”—help reduce the negative stereotypes that often surround neurodivergent individuals. This shift in language can lead to more inclusive environments in schools, workplaces, and communities where people feel respected and accepted for who they are, rather than marginalized or excluded because of how they think or interact with the world.

Amplifying Neurodivergent Voices

One of the most significant ways language influences inclusion is by amplifying the voices of neurodivergent individuals. When we use the terminology that people prefer—whether it’s identity-first or person-first language—we demonstrate that we see them as the experts of their own experiences. This practice of listening and using preferred terms is an act of allyship that shows respect for their identities. It signals that neurodivergent individuals are not defined by a condition, but rather by their full, complex humanity. By making space for these voices, we contribute to a more equitable representation in society, whether that’s in media, education, or policy.

Advocacy Starts with Awareness

Small changes in language may seem insignificant, but they are the first steps toward larger systemic changes. Language has the power to reshape attitudes, influence policies, and spark conversations that lead to meaningful change. When we embrace inclusive language in everyday interactions, we contribute to the shift toward greater acceptance in schools, workplaces, and the media. For example, educators who use empowering language in classrooms help students develop more positive self-concepts, while workplaces that adopt inclusive terms create more supportive environments for neurodivergent employees. As more people use respectful, inclusive language, it challenges outdated assumptions and encourages society to adapt to the needs of neurodivergent individuals.

In the long term, these shifts in language can influence broader societal changes—shaping policies, media portrayals, and even laws that recognize and support the rights of neurodivergent people. By being mindful of the words we use, we become part of a collective movement for justice, equality, and inclusion.

Conclusion

Language is not just a tool for communication—it’s a powerful force for shaping how we view and treat one another. The words we use to describe neurodivergence influence societal attitudes, challenge stereotypes, and create spaces where neurodivergent individuals can thrive. By choosing language that respects and empowers, we take active steps toward fostering inclusivity and reducing stigma.

As we move forward, it’s essential to be mindful of the language we use, to listen to the preferences of neurodivergent communities, and to embrace terms that honor their identities and experiences. Small changes in our language today can lead to greater understanding and acceptance tomorrow.

Let’s commit to being intentional with our words and continue learning from neurodivergent voices. The words we choose today can shape a more inclusive tomorrow.